The Main Empiricists

Francis Bacon (1561-1626)

A New Method Influence of Isaac

Newton Bacon &

Shakespeare

John Locke’s key influential works are ‘Two Treatises of Government’ (1689) and ‘An Essay Concerning Human Understanding’ (1690).

Although though many of Locke's conclusions have been cast aside by contemporary philosophers the spirit of his inquiry remains with us today: the exploration of what is possible for human minds to know and those areas that cannot be known. “Father of Empiricism” 'Human Understanding' comprises four books: Dr. Arthur Holmes, professor of philosophy, Wheaton college, outlines Locke’s tenuous position: "Setting the stage that way Locke is opening himself up to problems about whether or not we can show that there are external material bodies outside the mind. Whether or not there are other minds other than one's own. Whether or not there is an objectively real God rather than just the idea of God. Whether or not if there are objectively real binding moral obligations rather than just our ideas…The fundamental question being ‘Can we know any more than appearances - phenomena - as distinct from reality in itself?’. That question is still with us in contemporary debates over realism and anti-realism”. Another important philosophic inquiry that

Locke addresses is the question of the justification of belief - a crucial epistemological issue in

contemporary philosophy. Professor Holmes informs that Locke is an 'evidentialist' – that one is justified to

believe something if and only if that there is evidence to supports ones belief. This outline review on ‘The

Main Empiricists’ ends with the Scottish Realist who justifies belief with ‘natural

belief’. Enlightenment

Influence Representational View of

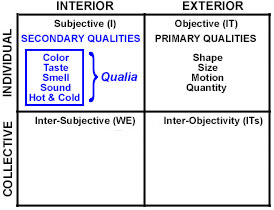

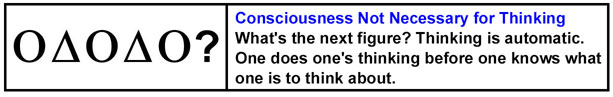

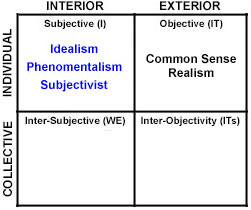

Perception A visualization of Indirect Realism shown below using Integral Theory’s AQAL model:

Political Theory –

Sovereignty of State & Individual Bishop George Berkeley (1685-1753)

Bishop George Berkeley (Bishop of Cloyne) was an Anglo-Irish philosopher and theistic idealist who advanced a theory he called ‘immaterialism’ (later known as ‘subjective idealism’) where external objects have actual being or real existence only when they are perceived by an observer. In his ‘A Treatise Concerning the Principles of Human Knowledge’ (1710), Berkeley took empiricism to its logical conclusion leading to the dismantling of Locke’s ‘Primary’ and ‘Secondary’ ideas of perception. As an empiricist, Berkeley believed that all knowledge comes from sensory experience and reflection, however, on the other hand, Berkeley attempts to prove that the outside world is composed solely of ideas. When Berkeley asks, “how do we know the shape of that orange?”, the Lockian reply is that it is a primary quality and that it is immediately perceivable. Berkeley’s insight was that you don't perceive some qualities of a object while totally disregarding others. You can't detect an orange’s shape without also detecting its color. You can't detect any of the primary qualities without considering the secondary ones. You can't see a colorless orange. You can't feel a texture-less orange. Remove all the secondary qualities and the orange is non-existent. Berkeley's conclusion: there's no such thing as matter, there's only perceptions. Berkeley’s ‘subjective idealism’ philosophy in

a nutshell: Esse est percipi – to be is to be perceived. At first glance of these claims the common sense man or the first semester philosophy student would advance that Berkeley’s position is not philosophical but psychological. In ‘The unconscious origins of Berkeley's Philosophy' (1953) professor of philosophy J.O. Wisdom comments, “Berkeley strove to expound a philosophy of Theocentric Phenomenalism, though with only partial success, while he succeeded at the same time in portraying a philosophy of Solipsism.” ‘Principles of Human Knowledge’ consist of 156 sections. Berkeley’s introductory #1 sets the tone of his project: to discover why the various sects of philosophy have fallen into “doubtfulness and uncertainties…absurdities and contradictions”. Bringing God Back

to the Center Stage To get God ‘back on stage’ Berkeley’s argument focused on the uniformities of our experiences. That we live in a common sense experience of common order and predictability. And the cause of that uniformity is a greater mind, a supreme intelligence, an infinite spirit – God. God is the other mind. God informs our minds and we participate in God's ideas; all our sensations and reflections are mental constructs, ultimately built by God. Dr. Arthur Holmes, professor of philosophy, notes that Berkeley’s God argument is “sort of an empiricist's equivalent of saying the human logos participates in the divine logos - the human mind participates in the divine mind. In his ‘A History of Philosophy’ courses (Wheaton college) Professor Holmes discusses an anecdotal story of one of his philosophy students who came from a Christian Science background. When they talked about Berkeley the student would say "that's the way I was brought up to think". Berkeley’s

Idealism

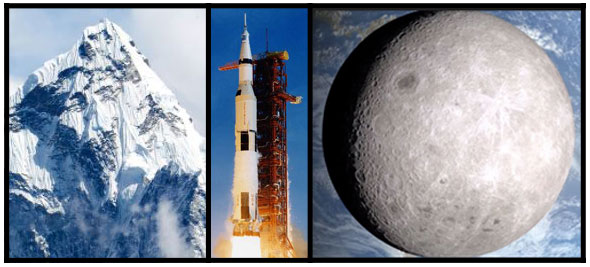

When Berkeley says “there is no material world” is he denying the existence of substances?; that there is no top to the highest mountain unclimbed or that there was no other side of the moon until the Apollo program? No, he would not say that. According to Berkeley the material world is a collection of attributes (big, blue, sweet, hot, cold) which are perceptions. Absent perception they are not attributes. For a thing to be, it has to have the potential for perception. So Berkeley asks, “when you take away the physical attributes or perception, what do you have?” “Nothing”. Berkeley's ‘immaterialism’ still begs the philosophical question: “Can something exist without being perceived?” Like the question – “If a tree falls in a forest and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound?” It depends on your philosophical point of view (POV). In regards to ‘objective’ knowledge of nature Berkeley and his 18th-century compatriots did not know about the concepts of time and space and that matter and energy are a relation rather than fixed separate entities. Moving from 18th-century Age of Reason to the 19th-century ‘Democratic Age' the emphasis shifts to innate resources, not knowledge, but the soul’s creative expression. As an empiricist Berkeley’s idealism focused on the passivity of the human mind as a recipient of sense data as opposed to the creative resources of the human spirit. The Problem of Evil

However, it is specious to claim that, since you do not have physical causes to explain physical evils, Berkeley’s ‘subjective idealism’, taken at face value, – which denies the ‘existence of material substances' – makes God responsible for the ‘evil’. Big problem there. Solving the ‘Problem of Evil’ cannot be accomplished with traditional theistic viewpoints. Contemporary idealist metaphysical ‘religions’ or ‘societies’ solve the problem with a higher understanding of ‘Divine Power’. The upshot is that is a dark planet for entities to learn to be positive in a negative world. Negativity abounds in the world. Did God create it? No. Man alone is responsible for it. Through free will choice, some people invert good to make a negative. We all have free choice of a path of Light or Darkness. The principle is almost like electricity: a rise in light or goodness is matched a rise in darkness or evil. What is evil? Basically greed (if it’s not god-centered). At the heart of every evil is greed (important to not confuse having abundance with greed; an abundance ‘for the greater good’). God is pure and constant in Their love. People are erratic and subject to petty behavior. Never ascribe to God such pettiness, for that makes God imperfect - that is not in Their nature. Earthquakes? Cancer? The metaphysical Gnostic reply on the former: ‘cleansing of the Earth’; the latter: your ‘exit point’ to go back ‘Home’. Metaphysical publications on evil: 'Journey of the Soul' series and ‘The Art of Being Yourself’. David Hume (1711-1776)

David Hume was a Scottish philosopher and modern skeptic who’s project was the exploration of the psychological conditions that define human nature – a “naturalistic science of man”. An approached that focused on the passions of human behavior rather than reasons. Hume was an agnostic and opposed the idea of an eternal soul and felt the question of God's existence was beyond human reason. He was one the early major thinkers to refute dogmatic religious and moral ideals in favor of a more sentimentalist approach to human nature. His belief system would help to inform the future movements of Utilitarianism and Logical Positivism. Hume’s significate work is the monumental “A Treatise of Human Nature: Being an Attempt to Introduce the Experimental Method of Reasoning into Moral Subjects and Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion” (1739–40). Due to the lack of public attention and acceptance (Hume lapsed into a semi-depression), he reworked the ‘Treatise’ and released ‘An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding’ (1748) and ‘An Enquiry Concerning the Principles of Morals’ (1751). In ‘A Treatise of Human Nature’ (1739) Hume ‘decapitates’ scientific morality (ethics) with his famous Hume’s Guillotine. Impressed by Isaac Newton's achievements in the physical sciences, Hume’s project became an empirical investigation into human nature and human psychology with the aim of discovering the "extent and force of human understanding". Against the rationalists, such as Descartes, Hume argues that the passions rather than reason are the causes behind human behavior. ‘Treatise’ consists of three Books: Hume's Theory Knowledge

Hume separated knowledge into two types – known

as “Hume’s Fork”: 2) Rational. Relations of Ideas – statements about ideas or values. Knowledge based solely on ideas or reason (rationalism). Rational statements are analytic, necessary (tautology) and knowable a priori – things we know through thought alone. Analytic a priori statements: ‘1+2=3’, ‘all bachelors are unmarried’, ‘triangles have three sides’. In Hume’s court the two prongs of his fork - empiricism and rationalism - can never touch. So according to David Hume only two valid propositions exist: 1) synthetic a posteriori and 2) analytic a priori.

Emmanuel Kant's ‘Critique of Pure Reason’ (1781) boils down to the justification for using both empiricism and rationalism. Kant rebuts “Hume’s Fork” and validates the justification by proving the existence of a synthetic a priori statement (not permitted by Hume). In essence Kant’s crossing of ‘Hume’s Fork’ bridged the idealists – those who thought that all reality was in the mind – and the materialists - those who thought that the only reality lay in the things of the material world (18th-century example of Integral Thinking). Kant referred to his new ‘worldview’ or philosophical system as “transcendental idealism” – knowledge that transcends mere consideration of sensory evidence and requires a higher understanding of the mind’s interpretation of sensory information. In ‘Critique of Pure Reason’ Kant held that the world of appearances (phenomena) is empirically real and transcendentally ideal. The mind plays a central role in influencing the way that the world is experienced: we perceive phenomena through time, space and the categories of the understanding (Quantity, Quality, Modality, Relation). Kant’s insight, supposedly missed by Hume, is that Time is not a stimulus that works on a sense organ, so time can’t be provided by experience. In the chapter ‘Pure Intuitions of Time & Space’ ‘pure’ signifies that time and space are a priori intuitions – a ‘higher understanding’, that. Causation

The Law of Associationism has been the engine

behind empiricism since the dawn of the Age of Enlightenment. The core principles Associationism: Even though the laws of science do predict events, Hume pointed out that is simply invoking the principle according to which the future is under the obligation to mimic the past. He informs us that experience does not tell us much. Of two events, A and B, we say that A causes B when the two always occur together, that is, are constantly conjoined. The subject of causation (‘Cause & Effect’)

can be vexing and lengthy discussion of it is beyond the scope of this web-site (refer to Stanford Philosophy

Encyclopedia for an academic review). Cause, according to many philosophers, means a force

that produces an effect. For Aristotle crucial understanding of proper knowledge of a thing is when we

have grasped its true cause and have avoided the delusion of causal fallacy otherwise known as post hoc ergo propter hoc fallacy (‘after this, therefore

because of this’). For example, the effect of "the rooster crows before sunrise” results in the fallacious

causal claim: “the rooster causes the sun to rise."

Hume’s position is exemplified in his explanation of billiard balls striking one another. He concludes that that we have absolutely no idea of why one event would cause another. When Hume see one billiard ball strike another billiard ball, he tells us 'I don't see some third term betwixt them'. That is, at the level of experience there is nothing that he can account for a 'cause'. There's movement, contact, movement – “can't see a cause” says Hume. (possibly similar to looking for a cause of why an apple falls from a tree – we can’t ‘see’ gravity). Looking at the billiard table all Hume can report is the motion of one ball striking another ball and the second ball having motion somehow imparted to it: “there is not, in any single, particular instance of cause and effect, anything which can suggest the idea of power or necessary connexion”. Some came to believe Hume while others, with an understanding of Newtonian physics, concluded that the second ball’s movement is not a case of post hoc ergo propter hoc fallacy. Scottish Realist Thomas Reid dismissed the ‘constantly conjoined’ position (and the subject of association) claiming that it appeared to require no other original quality of mind but the power of habit to explain the spontaneous recurrence of trains of thinking when they become familiar by frequent repetition. Another shortcoming of the ‘constantly conjoined’ principle is where superstitions can arise (“I wear my special cap at the game because my team wins more”). Problem of Induction

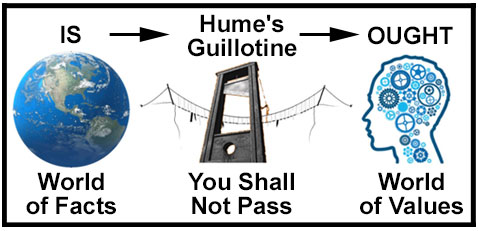

The astronomer cannot guarantee that the sun will rise tomorrow. The probability that the sun will rise tomorrow is so enormously large and from a common-sense point of view the matter is certain. However, the truth remains: the probability that the sun will fail to rise tomorrow is not zero. It is computable and from a scientific viewpoint sunrise cannot be guaranteed. Is Hume skeptical about science’s ability to predict things? Georgetown University professor Daniel N. Robinson comments: “No, Hume is not being skeptical, he simply wants to record the psychological dimension of all we know, all we feel, all we value and outside the human context of thought and feeling everything is in a shadow.” Hume argued against moral absolutes. He speculated that people’s ethical behavior toward and treatment of others is compelled by emotion, sentiment and passion – both positive (eg, love, happiness, interest) and negative (eg, fear, greed, envy). And that people are generally inclined to positive toward behaviors that result in desirable outcomes. Hume’s Guillotine: Is-Ought Gatekeeper Hume was the first to point out the Is-Ought question (Hume’s Guillotine) which in essence disconnects (‘decapitates’) scientific moralism's notion that knowledge of empirical facts or premises (‘what is’) dictates human values or moral statements (‘what ought to be’). A statement using IS describes the world (descriptive or positive statement). A statement using OUGHT prescribes value judgments (prescriptive or normative statement). In his lecture titled "Maps of Meaning: The Architecture of Belief" (2017), Dr. Jordan Peterson comments on Hume’s Is-Ought: “Simply knowing the objective facts does not tell you how to implement those facts in your life…You could say that is a necessary consequence of the scientific endeavor. One of the things you're trying do as a scientist is to strip away the value of the object – ‘I don't care what your idiosyncratic notion of what the object is - I want to know how you perceive the object such that everyone else will perceive it that way’. That (view) takes the subjectivity completely out of it. The (scientific method) does not have a morality in it…I buy Hume's argument - you can't derive an ought from an is – but it is a problem. You have factual knowledge but you don't know how to implement it ('Problem of Knowledge'). Should you spend money on AIDS research or cancer research or higher education? How can you calculate that rationally? You can't - you don't have the information at hand. For example, the UN has a list of important things to do to help the world - but there is no agreement on the order.” Metaphysical ‘Is-Ought’ example where the ‘IS’

is subjective, rather than objective: The metaphysical ‘What Is’ premise takes the position that something innate within us (‘divine within') allows us to recognize what is morally right or wrong. Skeptic: Where does ‘divine within’ come

from? Les Demoiselles d'Avigon - Beauty or Beast?

Hume’s Inconsistent View on

Religion Hume’s Solitude Thomas Reid will fixate on that thought and say, “so we see that Mr. Hume’s philosophy is very much like a hobby horse, which a man is ill and keep at home with him and ride to his contentment. But should he bring it into the marketplace, his friends would quickly empanel a jury and confiscate his estates. That is to say, Reid’s common-sense philosophy puts a certain requirement on the philosopher – namely the willingness to live according to the terms of his philosophy.” The Scottish School of Common Sense Realism

Scottish Common Sense Realism was a school of philosophy that sought to defend naive or direct realism against philosophical paradox and skepticism found within the likes of British empirical philosophers and the ‘Theory of Ideas’ system that began with Descartes' concept of the limitations of sense experience. The prominent founder of Common Sense Realism was Thomas Reid (1710-1796), known as “The Father of Common Sense Philosophy”. Reid’s “An Inquiry into the Human Mind on the Principles of Common Sense” (1764) argued that Common Sense is much closer to the truth of things than the philosophical tradition of the “Idea Theory” that preceded from the British Empiricists and Descartes. Common Sense Realism From a nature perspective, some say Darwinian, Reid uses the ‘lowly caterpillar’ analogy to explain how the principle of common sense operates: the lowly caterpillar will crawl across a thousand leaves until it finds the right one for its diet. From a societal perspective Reid’s Common Sense does not suggest ‘wisdom of the crowds’ prevailing opinions or the settled ethos of a given community. From an individual perspective Common Sense reflects the beliefs of the 'non-philosophical' man who possess, more often than not, a greater wisdom than the academic ‘philosophical’ man. Reid has largely been forgotten. Common Sense Realism was very popular in the 18th and 19th centuries. Very influential in French secondary schools. Before the Civil War, every major American college was a disciple of common sense realism. In an Oxford University lecture on 'Reid's Critique of Hume' Professor Daniel N. Robinson comments: “The reason why we are not studying Thomas Reid is because his directness, his utter accessibility, his resonance with core principles of common sense carried by everyone 24 hours a day in the serious business of living life just doesn't look sophisticated enough to maintain close philosophical attention. That is to say Reid does not know how to go about confusing you. And that renders his entire position suspect.” Common Sense Realism is not without it shortcomings as in any theory of philosophy or theory of social science has. CSR’s fall from ‘philosophical attention’ has been ascribed to the ‘thousand cuts’ of a radical academic (eg, post-structuralists) agenda: rejection of the U.S. Founder's vision, the Constitution, the Electoral College and the Founding Fathers themselves. Opposition to Idea Theory

Common Sense Realists reject the skepticism of the “Idea Theory” on the grounds that it is absurd and incompatible with common experience. The “Idea Theory” is a representational theory - the view that the immediate object of our mental awareness is the idea in our minds. The content of our own mind is all we have direct awareness of.

Idea Theory: According to Reid and Common Sense Realists the ‘Idea Theory’ is fiction - productions of philosophical imagination. And that Ideas do not have Secondary qualities, as expounded by Locke. Ideas, literally, don't smell. Its roses that smell. To talk about the subjectivity of qualities seems to falsify what we seem to know already.

In philosophical jargon, Reid is arguing a presentational view of perception rather than a representational view of the Idea Theory. The presentational view is an empirical philosophical view that objects are not represented to us by ideas but are directly presented to the consciousness. Professor Robinson continues: "To Reid, being a strict Newtonian and Baconian, this is not the way science is done and why philosophy gets a bad name – of people sitting around spitting off conjectures and theories with absolutely no access to methods by which to determine a systematic and scientific way whether the theory is grounded or groundless." AQAL View

Whew! Either you’re thinking, “what in the wide-world of ‘woo-woo’ is going here?” or ‘I’m glad I didn’t major in philosophy!”. A visualization of Common Sense Realism along with other philosophical views discussed is shown below using Integral Theory's AQAL model:

The question that divides a Common Sense Realist from a phenomenalist or a subjectivist: when you look at an object that you strongly regard as being in the external world, is the result of that inspection an impression or idea or is it the registration of the object itself? As opposed to the 'Idealist' the realist believes in the independent existence of matter where matter is primary and mind is secondary. The concept that whether matter is mind independent or mind dependent is core to the “Mind over Matter” versus “Matter over Mind” debate. Integral theorist Ken Wilber sheds light on the representation paradigm and the limitations of empirical map making of the sensory world. Using the ‘embrace and extend’ philosophy the point is not to totally reject all values of the ‘Enlightenment’ movement - to not reject a ‘label’ but to recognize the good of its legacy amongst today’s and even tomorrow’s values. Natural Beliefs

Reid argued that we have natural proclivities toward belief - natural beliefs. From our natural beliefs about the existence of the physical world, order-ness of the physical world and the magnificent order of the world of nature. The natural belief of mankind’s desire for freedom can be seen in ‘self-evident’ truths of the Declaration of Independence. Reid posits that from natural beliefs we can produce deductive arguments for the existence of God. Natural Theology is a branch of theology based on reason and ordinary experience without reference to supernatural revelation. Not a novel ideal - Descartes had a theistic justification for trusting one’s rational faculties. So did Locke. 80-20 Rule

z |