Epistemology The term ‘epistemology’ is from Greek, from episteme- (knowledge) + logos (reason) or the study of knowledge to gain knowledge. Epistemology’s extensive history begins with Plato who strove to know the difference between knowledge from opinion. He defined knowledge as in “Justified True Belief”, in contrast to doxa, common belief or opinion. The dictionary defines opinion as "belief stronger than impression and less strong than positive knowledge". It can be claimed knowledge is an opinion plus something – truth, justification, reliability, etc.; hopefully an opinion that is not a ‘bad’ or biased and that an acceptable opinion is accountable to fallibilism. After Plato John Locke's

epistemology was an attempt to understand the operations of human understanding. Immanuel

Kant's epistemology was an attempt to understand the conditions of the possibility of human

understanding, and Bertrand Russell’s epistemology was an attempt to understand how modern science could be

justified by appeal to sensory experience. There are two epistemological traditions: Empiricism & Rationalism - theories on the sources of knowledge. There is no single definition of knowledge. There are numerous theories to explain it and there are many ways to classify knowledge (types, classes, qualities, structures). Many elaborate distinctions exist. For example, knowledge can be either explicit (self-conscious) or implicit (hidden from self-consciousness). It can be either propositional or non-propositional. Propositional knowledge can be divided into empirical (a posteriori) and non-empirical (a priori) knowledge. Genetic epistemology is a study of the origins of knowledge. The ‘twin-sister’ to epistemology is ontology: the study of the nature of being, existence or the ultimate nature of reality – the “modes of being”. Ontology precedes epistemology and methodology. Empiricism and Rationalism are individualist theories of knowledge, whereas historicism is a social epistemology (the collective). While historicism also acknowledges the role of experience, it differs from empiricism by assuming that sensory data cannot be understood without considering the historical and cultural circumstances in which observations are made. Some epistemological historians have argued that the empirical sciences need to give up attempting to look for a priori presuppositions of knowledge; to abandon a static view of knowledge and its justification, adopting instead a dynamic picture of science, looking to history for reliable methods of revising beliefs. A few key questions that concern the study of

epistemology are: Subject &

Object Schopenhauer, and the many influential philosophers before him, makes the premise that the world consists of Objects which are perceived by Subjects. The Subject-Object division has been a longstanding philosophical investigation with philosophers inquiring on how subjects relate to objects. Inquiring on the Subject-Object division gets

us back to the question on how to validate true knowledge. The valid knowledge problem has two

aspects: The dictionary defines subjective as "the impression which an object makes on the mind." A concept or idea is subjective: an external object is the percept while the impression in one’s mind is the concept. Subjective always means something that receives. The deepest issue of the philosophy of mind is this: how is it possible that a material system such as the human brain/body gives rise to subjective experiences of the mind? Current theories of mind explain certain structures or functions at work, but they cannot explain this fundamental ‘phenomenon’ – subjective experience. The skeptic may ask, “how do you know there is subjective experience in the first place?”. This is axiomatic. It is a given. A fundamental fact we have to accept. Schopenhauer, et al, would say it is the very fact that brought us the idea of consciousness! Without it, we would never have discovered that thoughts and feelings existed. The Great Chain of Being 1. God The American spiritual writer and philosopher Ken Wilber developed a similar macro concept called the "Great Nest of Being" – a holarchy with five levels: Spirit, Soul, Mind/Emotion, Body and Matter. Wilber claims that the “Great Nest of Being” belongs to a culture-independent "perennial philosophy" traceable across 3000 years of mystical and esoteric writings. Objective Being |

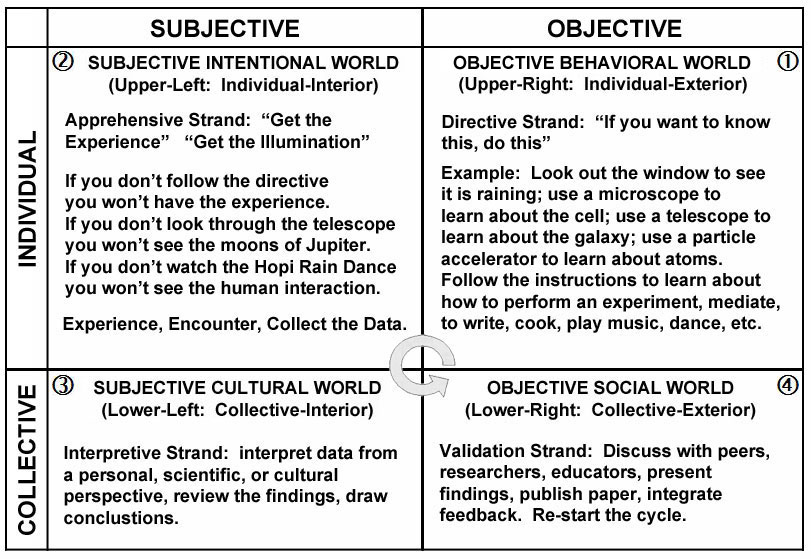

Ontology/Cosmos: God, Archetypes/Ideas, Matter ‘AQAL’ – Easy to Use Epistemological-Ontological Map Knowledge validation follows the cycle:

(1) Directive, (2) Apprehension, (3) Interpretation, (4) Validation. To illustrate the utility of the AQAL matrix, let’s consider the philosophical tenet known as ‘subjectivism’ which has be attributed to Descartes. Subjectivism is the belief that “our own mental activity is the only unquestionable fact of our experience”. Subjectivism holds subjective experience to be the supreme fundamental of all measure and law. Thus, if we are to read “The world has no existence whatsoever outside the human imagination – it’s all ghosts”, AQAL helps us to understand that this is very extreme position on the ‘subjective’ quadrant, to the point of rejecting natures within the objective quadrant. This is similar to solipsism, another extreme form of subjectivism, where the subject is unsure of any knowledge outside one’s own mind. Other AQAL examples: Phenomenalism, Key Philosophical Words In general, the AQAL model forces our philosophies to be more integral and to avoid unhealthy extreme positions. z

|