The

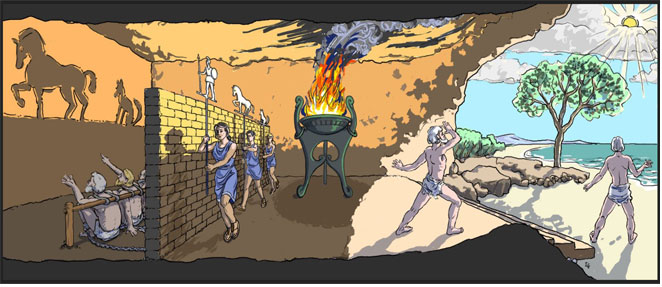

Republic The Republic is Plato’s plea that philosophy take over the role art played in Greek culture. The main concerns of Platonic philosophy were how to tackle the problem of knowledge or truth and the problem of conduct (goodness). Plato’s ‘ideals’ have origin in his Scala Naturae or 'The Great Chain of Being'. The Problem of Knowledge: Allegory of the Cave In the Republic’s ‘Allegory of the Cave’ a

group of people have been chained to a wall for all their lives. They only see images casted onto a blank

wall. The ‘philosopher’ is one who breaks free of his chains, ventures outside in the sunlit world to

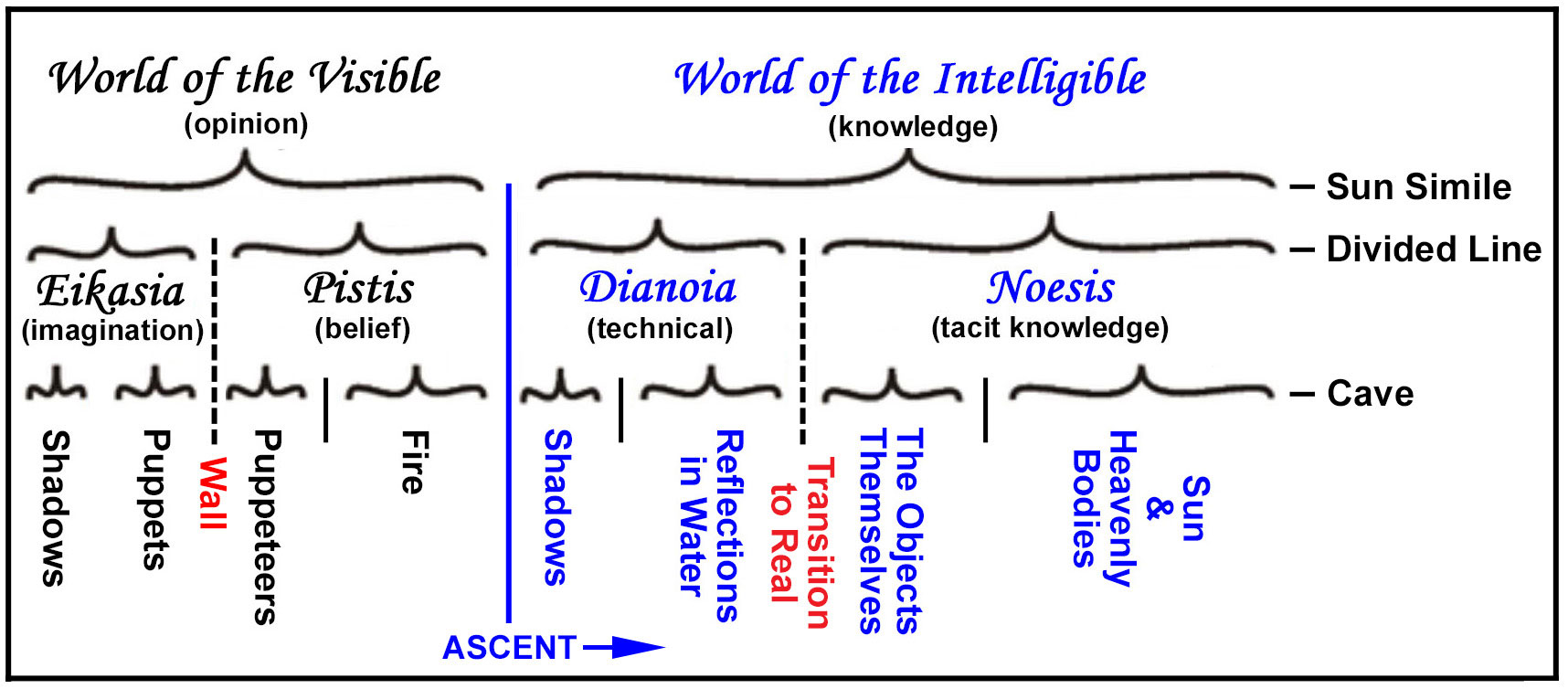

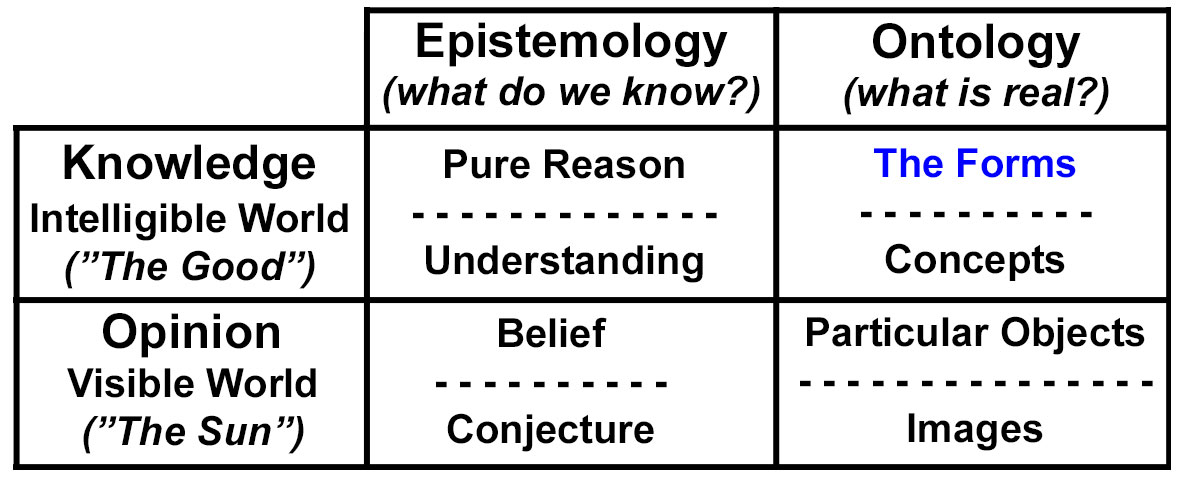

receive enlightenment, education and wisdom. The illustration below ties the “Allegory of the Cave” to the other allegories from Socrates and Plato: ‘Sun Simile’ and the ‘Divided Line’. The world is divided into two realms: 1) the visible - the physical universe which we grasp with our senses, 2) the intelligible - the metaphyscial universe which we only grasp with our mind. Inspired by Socrates the 'Analogy of the Divided Line' is the cornerstone of Plato's metaphysical framework. It illustrates the grand picture of Plato's metaphysics, epistemology and ethics all in one.

The Allegory of the Cave has other allusions: the death of Socrates and Plato having to deal with angry liberated cave prisoners who are upset at being freed from their illusions; the Noumenal-Phenomenal distinction; even the cave as the main principle in the movie 'The Matrix'. The Problem of Conduct: Allegory of Charioteer

In the "Ring of Gyges", Book 2 of the 'Republic', the owner of the ring is granted the power to become invisible at will. Plato is exploring whether an intelligent person would be just if one did not have to fear any bad reputation for committing injustices. The myth of Gyges is a story how absolute power corrupts. The lure of the ring of invisibility hoodwinks the owner into believing that nothing of ethical consequence can follow – so it’s ok to kill the King, rape the Queen and take over the realm. Behavior similar to Ovid’s insolent god-like creatures. The spiritual upshot is that, in the end, there is compensation and retribution for all good and evil deeds done on Earth and that the soul knows the transgression, otherwise the owner is dark. Plato’s “Ring of Gyges” inspired J.R.R. Tolkien’s 'Lord of the Rings' In his dialogue ‘Phaedrus’ Plato uses the Chariot Allegory to explain the importance of rational power in one’s conduct. The supremancy of reason – in terms of what we ought to do. The

Forms

The lowest level (Lower Left quad) represents ‘the world of becoming and passing away’. The world of physical things themselves and their shadows and reflections. The illusion (eikasia) of our ordinary experience and the belief (pistis) about discrete physical objects which cast their shadows. The highest level (Upper Right quad) represents Plato’s Form that which is perfect, eternal and changeless, existing outside space and time. Only the Forms are objects of knowledge, because only they possess the eternal unchanging truth that the mind - not the senses - must apprehend. The Forms are eternal truths which are the source of all Reality. In real life, beautiful things grow old and die. The Form “Beauty” is eternal – it never dies. For Plato to truly understand the Forms (Ideas) the philosopher must also understand the relations of Ideas to all the levels (‘quads’) to be able to know anything at all. The concept that knowledge cannot be gained through sensory experience – Plato’s ideal of the Forms – remerges in late European 17th-century rationalism begun by Descartes. Likewise, the concept that knowledge can only be gained through sensory experience is seen in empiricism begun by Sir Francis Bacon. American philosopher Ken Wilber’s AQAL framework has a similar structure to Plato’s ‘Worlds’ where the right planes or ‘quads’ represent the senses (the ‘exterior’) and the left quads represent ‘what we grasp with our minds’ (the ‘interior’). Wilber’s innovation includes an ‘Individual-Collective’ second dimension where the collective embraces attributes such as shared values, meanings, language, relationships, historicism and cultural backgrounds. The Ideal

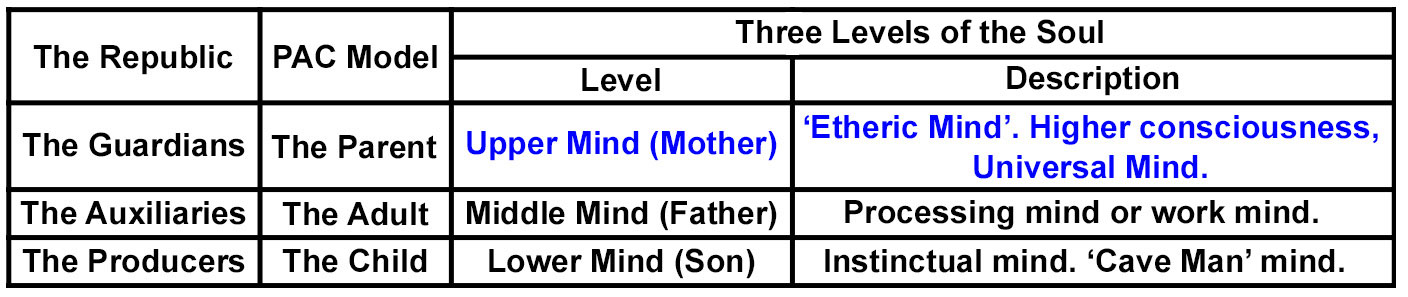

State The matrix below illustrates the comparison between Plato’s Aristocracy classes to Dr. Eric Berne's Transactional Analysis PAC model and the Three Levels of the Soul.

2) Timocracy Socrates is asked, “Where are we going get them – these guardians of the state?” He replies, “By giving birth to them. If they don’t measure up, we dispose of them, the State doesn’t need them”. Dr. Daniel Robinson, professor of philosophy (Georgetown Univ), comments: “So explains Bertrand Russell’s ‘fascist’ interpretation…Plato proves not to be the happy-go-lucky, simple advocate of nude wrestling and exercise, but a much tougher - even a ruthless - advocate of the measure to insure the survival of the state” (in the contemporary university-state system the new reply appears to be, “If the students don’t measure up, we’ll make financial slaves of them”). Socrates turns the table and asks the great question: “Can virtue be taught?” Professor Robinson continues, “Virtuosity is a 24/7 affair. It is a universal principal – so it is not accessible to the senses. The senses can only pickup particulars, they cannot pickup universals. Teaching by showing, things you can touch, cannot be universals. You can’t point at that which is universal. How can you teach virtue if you can’t show something?, can’t point to it?...We can’t teach virtue in the empirical sense of pointing to virtue, but, perhaps, we can point to virtuous acts – to persons who act in a virtuous way. A child will not understand by looking at acts of courage & heroism & sacrifice (women's suffrage); cannot work unless the audience is prepared...In Plato's Republic we have the foundations of an elitist position – who shall be virtuous? A convenient fiction of men of gold, of silver, of brass and of iron – the life of virtue is not available to anybody and everybody. It takes a certain kind of person.” In

Closing Kant took these questions and composed a series of works that strove to quell the disparity between the two stations of thought (eg, the world of the 'Visible' and the 'Intelligible'). Kant formulated a world where humans are confined to their perceptions and that these perceptions help us to understand our world and are necessary for us to understand our ability to reason. Without reason there would be no way to explain what we perceive and without perception there would be no use to use reason for we would not have any questions. Every question we have today was presented through our perceptual experience. Is it true that “nobody is born with innate knowledge”? The idea that knowledge, ideas, and concepts including talents and skills are only learned from experience? Rationalism argues the idea that human beings have some universal knowledge, such as reasoning, mathematics, and ethics, which is then forgotten at birth and only uncovered by experience derived from the senses. Empiricism conveys the opposite idea, stating that our minds are blank slates from birth, with sensory experience providing the opportunity to deduce and reason more complex ideas. Plato’s Allegory of the Cave argues that there is a possibility that what we are perceiving right now is actually false and we haven’t realized it yet. Descartes challenged empirical belief – the beliefs formed through our senses.

|