A Priori Zen

In "Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance" (Robert M. Pirsig, 1974) the author discusses a priori during the journey through the ‘High Country of the Mind’: Kant says there are aspects of reality which are not supplied immediately by the senses. These he calls a priori.

An example of a priori knowledge is “time”. You don’t see time. Neither do you hear it, smell it, taste it or touch it. It isn’t present in the sense data as they are received. Time is what Kant calls an “intuition”, which the mind must supply as it receives the sense data. The same is true of space. Unless we apply the concepts of space and time to the impressions we receive, the world is unintelligible, just a kaleidoscopic jumble of colors, patterns, noises, smells, pain and tastes without meaning. The a priori concepts of time and space provide a kind of screening function for what sense data we will accept. When our eyes blink, for example, our sense data tell us that the world has disappeared. But this is screened out and never gets to our consciousness because we have in our minds an a priori concept that the world has continuity.

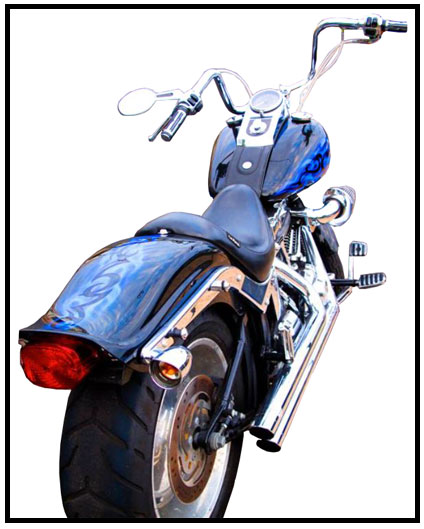

If I say the motorcycle is made of metal, Hume asks, What’s metal? If I answer that metal’s hard and shiny and cold to the touch and deforms without breaking under blows from a harder material, Hume says those are all sights and sounds and touch. There’s no substance. Tell me what metal is apart from these sensations. Then, of course, I’m stuck. But if there’s no substance, what can we say about the sense data we receive? If I hold my head to the left and look down at the handle grips and from wheel and map carrier and gas tank I get one pattern of sense data. If I move my head to the right I get another slightly different pattern of sense data. The two views are different. The angles of the planes and curves of the metal are different. The sunlight strikes them differently. If there’s no logical basis for substance then there’s no logical basis for concluding that what’s produced these two views is the same motorcycle. Now we’ve got a real intellectual impasse. Our reason, which is supposed to make things more intelligible, seems to be making them less intelligible, and when reason thus defeats its own purpose something has to be changed in the structure of our reason itself. …It’s quite the machine, this a priori motorcycle. The sense data confirm it but the sense data aren’t it. The motorcycle that I believe in an a priori way to be outside myself is like the money I believe that I have in the bank. If I were to go down to the bank and ask to see my money they would look at me a little peculiarly. They don’t have ‘my money’ in a little drawer they can pull open to show me. ‘My money’ is nothing but some east-west and north-south magnetic domains in some iron oxide resting on a roll of tape in a computer storage bin. But I’m satisfied with this because I have faith that if I need the things that money enables, the bank will provide the means, through their checking system, of getting it. Similarly, even though my sense data have never brought up anything that could be called “substance” I’m satisfied that there’s a capability within the sense data of achieving the things that substance is supposed to do, and that the sense data will continue to match the a priori motorcycle of my mind. I say for the sake of convenience that I have money in the bank and say for the sake of convenience that substances compose the cycle I’m riding on. The bulk of Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason is concerned with how this a priori knowledge is acquired and how it is employed. Kant called his thesis that our a priori thoughts are independent of sense data and screen what we see a ‘Copernican revolution’. By this he referred to Copernicus’ statement that the earth moves around the sun. Nothing changed as a result of this revolution, and yet everything changed. Or, to put it in Kantian terms, the objective world producing our sense data did not change, but our a priori concept of it was turned inside out. The effect was overwhelming. It was the acceptance of the Copernican revolution that distinguishes modern man from his medieval predecessors. What Copernicus did was take the existing a priori concept of the world, the notion that it was flat and fixed in space, and pose an alternative a priori concept of the world, that it’s spherical and moves around the sun; and showed that both of the a priori concepts fitted the existing sensory data. Kant felt he had done the same thing in metaphysics. If you presume that the a priori concepts in our heads are independent of what we see and actually screen what we see, this means that you are taking the old Aristotelian concept of scientific man as a passive observer, a “blank tablet" and truly turning this concept inside out. Kant and his millions of followers have maintained that as a result of this inversion you get a much more satisfying understanding of how we know things." Note: Pirsig's "QUALITY-Romantic-Classic-Quality-Preintellectural-Intellectural-Reality-Subjective-Objective-Reality" map could also be view as another topology of the "Great Chain of Being" map. z |