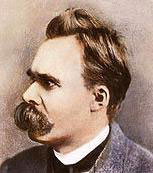

Fredrick Wilhelm Nietzsche (1844-1900) "No one can construct for you the bridge

upon which precisely you must cross the stream of life, no one but you yourself alone" ―

F.W.N.

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche was a 19th-century German philosopher, poet, cultural critic and classical philologist (the study of language in written historical sources). He wrote critical texts on religion, Christian morality, contemporary culture, philosophy and science. Background Nietzsche’s key works include: The Birth of

Tragedy (1872), The Gay Science (1882), Thus Spoke

Zarathustra (1883-85), Beyond Good and Evil (1886), On the Genealogy of Morals and Ecce Homo

(1887), The Will to Power (1901). Historical Context

Having been schooled in the classics and German romanticism Nietzsche languished in the backwaters of political stagnation after 1848. Over time he turned more to the right drawn by the 'siren call' of cultural elitism (Nietzsche boldly stating ‘knowledge and study is privilege of the few’); the mystical elements of German Lebensphilosophie ('philosophy of life') and the pseudo-science of eugenics. Nietzsche’s profound disappointement due to the unification of Germany (outcome of the Franco-Prussian War, 1870) is found in the expressions in his later writings. The rise of the Paris Commune (1870-1871) shocked Nietzsche who warned that universal education could lead to communism. In 'Thus Spoke Zarathustra' he writes, "That everyone is allowed to learn to read at length spoils not only writing but also thinking". Superman & The Will to Power

The Superman represents Nietzsche’s archetype for a meaningful life where the ‘Ubermensch’ is the brave warrior-hero who transcends society in pursuit of freedom and what is good – all in the name of living a creative life and a ‘will to power’. Nietzsche is completely hostile to the idea of equality as he views it as crushing freedom and the will to power. Nietzsche’s world is not a world of, in the words of Mathew Arnold, ‘sweetness & light’. There is a dark side to ‘the will to power’. It is a world of light & dark; of opposing polarities and opposing tendencies. The Superman’s ‘Will to Power’ mirrors the destructive side of the Greek primordial god Eros: the force behind rape and pillage; behind victory and conquest. The Ubermech or ‘Superman’ is a loaded term. Philosophy professor Daniel N. Robinson (Georgetown University) comments: “In ‘Zarathustra’ Nietzsche seems to be indicating that there’s some sort of super race out there just waiting take over. You could almost see Nietzsche as a prelude to Hitler and the Nazis. The closest he gets to actually calling someone the Ubermensch is Goethe". Order & Chaos

The Yin-Yang image is an apt symbol for the ‘Apollonian-Dionysian’ dance. Canadian professor of psychology Jordan Peterson finds insight between the two: "The Taoist believe that the symbol represents 'being'. Now, being is not the same thing as objective reality, Being is what you experience as a conscious creature. That's being. For the Taoist being is made up of these two elements - order and chaos...things you understand and things that work the way that you expect them to, and things you do not understand and that can pull the rug out from under you at any moment...These are symbolic representations of the most unchanging elements of being - the most real...in fact they're hyper real, because one of the things that defines real is that it's permanent...it's part of the existential landscape of human being...The reason that the white paisley has a little black dot in it and [vice versa] is that the Taoist recognized that chaos can turn to order at any moment, so a new order can rise out of a chaotic structure. What's the optimal position? The line between the two. If it's too orderly then it's totalitarian, and if it's too chaotic then it's disgust and fear and emotional pain and depression.” Nihilism & The (False) God is Dead

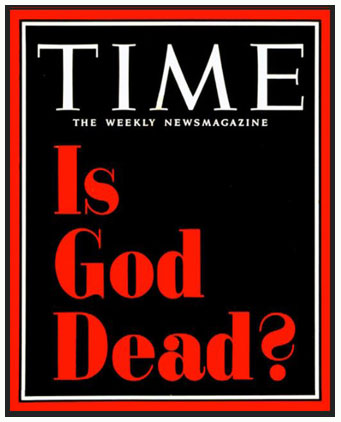

In ‘The Gay Science’ Nietzsche writes: "After Buddha was dead his shadow was still shown for centuries in a cave - a tremendous, gruesome shadow. God is dead; but given the way of men, there may still be caves for thousands of years in which his shadow will be shown. And we still have to vanquish his shadow, too." For Nietzsche good and evil are childish notions and what really matters is will and choice. That self-assertion is the highest value and power decides important questions rather than reason. Nietzsche’s critique against Buddhism and the non-egoistic ascetic is his famous saying “God is Dead”, which was his way of saying that the idea of God is no longer capable of acting as a source of any moral code or teleology (an account of a given thing's purpose). The thinking, spiritual woman and man, sidestepping Nietzsche’s ‘de-constructional’ claim that rational explanations don’t work, interpret Nietzsche’s God as an ‘Old Testament God’ − an imperfect, false god with human qualities: mean, nasty, hateful, vengeful. Better if Nietzsche said, “The False God is Dead”. Amen.

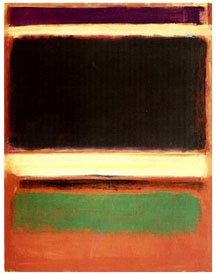

Influenced by Nietzsche’s ‘The Birth of Tragedy’ American abstract painter Mark Rothko found inspiration from classical Athenian tragedies to transcend pessimistic and nihilistic point-of-views (POVs) that the world is fundamentally meaningless. The tragedies taught the Greek spectators that they are infinitely more than petty individuals, finding self-affirmation not in another life, but in the terror and ecstasy of the opposition of the rational against the emotional in the backdrop of the abstract against the primal. Proclaiming that "the exhilarated tragic experience is for me the only source of art", Rothko strove to create an art that could free modern man’s spiritual and creative energies. Where the dread of the abyss of human suffering is transcended by the joyous affirmation of an enlightened meaning of one's existence. Religious Herd

Saddened by his inability to move the herd of people in the marketplace, Zarathustra, resolves not to try to convert the multitudes, but to speak to those individuals who are interested in separating themselves from the herd. Leaving the herd has never been a rational decision in the history of mankind; it provides people with protection, comfort and community - people want to belong and be accepted. The downside? Compliancy: the herd lives without questioning the values and purposes of the herd. In the BBC documentary 'The Long Search' Ronald Eyre summaries the downside of the herd: "Every idea, every statement, every institution has a tendency to harden up and go dead." Nietzsche views the 'ascendent' Christianity as weak. His character, Zarathustra, advocates a struggle where the Ubermensch challenges the otherworldly Christian values. Nietzsche views Christianity as a ‘religion of servitude and guilt’ designed to keep people in their place, to set a limit on their progress, to set a limit on the expression of their feeling. He had a strong contempt for Christ because of the mercy He showed to the weak and outcasts: “What is more harmful than any vice? Practical sympathy and pity for all the failures and all the weak: Christianity.” Some academics have argued that the infamous Nazi cruelty can be traced to Nietzsche’s criticism of Christ’s teaching of loving the downtrodden. Nietzsche's most trenchant critiques of traditional morality is that most of what passes for morality, isn't morality - its cowardice. The Christian idea of “turning the other cheek and let someone hurt you” was never the true Christian idea where the meek dutifully reply, “Thank you very much.” No! Nietzsche was against that. There are stories of nuns, ministers and others, even today, who died of some horrible thing; they ate themselves alive with it. Nietzsche must have recognized genuine weakness among the ‘pious’: a lack of righteous anger; being ‘virtuous’ when they allowed others, because of their faith, to hurt them and allowed themselves to become a doormat to the world. Religious academics point out that Nietzsche wrongly viewed the Christian faith, like many atheists, as an epistemology versus a response to previously acquired knowledge: “But when faith is thus exalted above everything else, it necessarily follows that reason, knowledge and patient inquiry have to be discredited: the road to the truth becomes a forbidden road”. Nietzsche goes on to say, “Whatever a theologian regards as true must be false: there you have almost a criterion of truth”. The Climb

The struggle of a ‘climb’ can be seen in Nietzsche’s view of life’s suffering: “self-loathing, the torture of mistrust, and the misery of himself to be overcome that is necessary for self-knowledge and, finally, a life of dignity” (Novus Tenet 1).

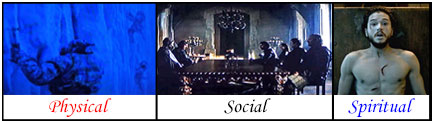

Climbing metaphors can be seen the medieval fantasy television drama series ‘Game of Thrones’: Physical, Social and Spiritual. A Christ allegory is seen in Jon Snow, the outcast protagonist, who is assassinated by his officers – a betrayal like Judas. Snow dies, is resurrected (by the Red Priestess Melisandre) and undergoes a great sacrifice to be a savior or a redeemer. Snow’s ‘spiritual climb’ – death by heroic sacrifice followed by a triumphant return – transcends his physical and social assents. On the Road to Post-Modernism

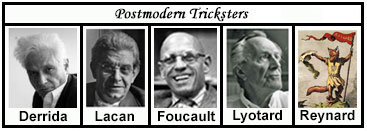

Nietzsche favored perspectivism which held that truth is not objective but is the consequence of various factors effecting individual perspective. When Nietzsche poses questions such as, “What about these linguistic conventions themselves?” or “Is language the adequate expression of all realities?”, he is championing the notion of perspectivism, the philosophical belief that interpretations and conceptions of truth depend on the perspective of the one who is observing; that there is no absolute truth outside our own perspective. The early beginning of postmodernism begins with the concept of perspectivism. In “The Closing of the American Mind” author Allan Bloom puts forth his complaint in the opening, “the contemporary university student talks as if there is no such thing as truth and falsity; right & wrong. Has no sense of personal identity and has no worldview to on which ground any of those things.” Bloom traces the source of the problem to the continental thinkers and value relativism. The late philosophy professor Dr. Arthur Holmes takes caution with Bloom’s ‘continental’ claim: “That's not the whole story. The influence is much from the positivist tradition with its assertion that the pragmatist tradition of only having an instrumental view of truth and meaning where values are just expressions of emotion.” The maxim “When the door closes, a window opens” suggests, possibly, a closing of some ‘analytic mind’ (hopefully not a rational one) and an opening of a ‘creative mind’. The character of Nietzsche’s philosophy or outlook is naturalism – a biological vitalism – that life is a creative force. Nietzsche’s ‘vitalism’ plays a strong role in whatever he says about human knowledge, human thought and epistemology – an ethos that later feeds into post-modernism. What is important is to maintain integral thinking - to embrace and extend the two kinds of human thought: analytic (Classical) and the creative (Romantic) (not right/left brain biology). In Closing

He lived his remaining years in the care of his mother until her death in 1897, then under the care of his sister. Nietzsche died at 56. Nietzsche’s death in 1900 is significant to many as the departure from modernism and most likely the reason for many scholars claiming that he was one of the most influential thinkers of the 20th-Century.

|