Postmodernism - A Brief Historical

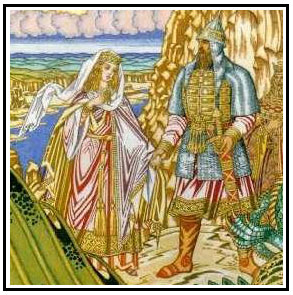

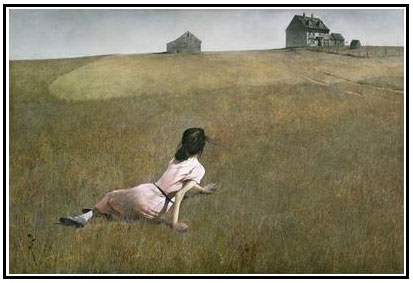

Background Romance William Rose Benet, The Reader’s Encyclopedia: “In medieval literature, a verse narrative recounts the marvelous adventures of a chivalric hero…In modern literature, from the later part of the 18th century through the 19th centuries, a romance is a work of prose fiction in which the scenes and incidents are more or less removed from common life and are surrounded by a halo of mystery, an atmosphere of strangeness and adventure”. Realism Chris Baldick, Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms: “A mode of writing that gives the impression of recording or ‘reflecting’ faithfully an actual way of life. The term refers, sometimes confusingly, both to a literary method based on detailed accuracy of description and to a more general attitude that rejects idealization, escapism, and other extravagant qualities of romance in favor of recognizing soberly the actual problems of life”. Realism was once a new, innovative form of writing (Daniel Dafoe (1660-1731); Samuel Richardson (1690-1761)) and it challenged the dominate current mode of prose writing – the Romance. One of the earliest novels, Cervantes’s Don Quixote (1605-15), parodies the romantic genre and survives in Gothic and fantasy fiction. Malcolm Bradbury, in Childs and Fowler: “Modernist art is, in most critical usages, reckoned to be the art of what Harold Rosenburg calls, ‘the tradition of the new’. It is experimental, formally complex, elliptical, contains elements of decreation as well as creation, and tends to associate notions of the artist’s freedom from realism, materialism, traditional genre and form, with notions of cultural apocalypse and disaster…We can dispute about when it starts (French symbolism; decadence; the break-up of naturalism) and whether it has ended. We can regard it as a timebound concept (say 1890 to 1930) or a timeless one (including Sterne, Donne, Villon, Ronsard). The best focus remains a body of major writers (James, Conrad, Proust, Mann, Gide, Kafka, Svevo, Joyce, Musil, Faulkner in fiction; Strindberg, Pirandello, Wedekind, Brecht in drama; Mallarme, Yeats, Eliot, Pound, Rilke, Apollinaire, Stevens in poetry) whose works are aesthetically radical, contain striking technical innovation, emphasize spatial or ‘fugal’ as opposed to chronological form, tend towards ironic modes, and involve a certain ‘dehumanization of art’. In “Modernism” (2000), literature professor Peter Childs

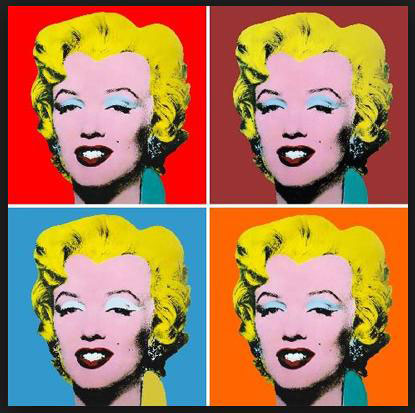

writes, “With regard to literature, modernism is most readily understood through the work of the avant-garde authors who write in the decades before and after the turn of the 20th century. It is a contentious term and should not be discussed without a sense of the literary, historical and political debates that have accompanied its usage…[Unlike realist writers like] Jane Austen, Charles Dickens or George Eliot…modernist writing ‘plunges’ the reader into a confusing and difficult mental landscape which cannot be immediately understood, but which must be moved through and mapped in order to understand its limits and meanings…Modernist prose is enormously compressed, which means that it ought to be read with the attention normally reserved for poetry or philosophy…[For example, in Samuel Beckett’s Murphy (1938), Beckett's] brief lines allude to complex ideas; comic set pieces enact philosophical theories; and there is little attempt to relate the extreme situations and mental conditions in the novel to anything the reader might consider to be representing ‘normality’. [Murphy’s] opening contains many of the features associated with modernist stylistics and preoccupations: a solipsistic mental landscape, an unreliable narrator, psychological and linguistic repetition, and obsession with language, a quest(ioning) towards ‘reality’, uncertainty in a Godless universe, the constraints of convention against the drives of passion and black humor.” “It is…perhaps both impossible and undesirable to speak of a single ‘modernism’, and the practice of referring to ‘modernisms’ dates back to the 1960’s. Some critics argue that the term is simply an imposition, applied after the fact to a small group of unrelated authors and a series of genuine movements such as imagism and vorticism….Modernism has predominantly been represented in white, male, heterosexist, EuroAmerican middle-class terms, and any of the recent challenges to each of these aspects either reorients the term itself and dilutes the elitism of a pantheon of modernist writers, or introduces another one of a plurality of modernisms”. “[Most of the points made in the 1970s, that ‘modernism’ is a specious label, are challengeable]. For example, that it is fundamentally Euro-American is open to immediate querying, when it can as persuasively be argued that modernism marked the regeneration of a tired Western artistic tradition by other cultures: African, African-American, Asian, Chinese, and, more generally, diasporic. Similarly, the view that modernist writers simply rejected or broke away from Victorian literature, for example, has been more and more challenged as critics point out connections with rather departures from the writings of such figures as Robert Browning, Walter Pater, A.C. Swinburne and even Rudyard Kipling”. Postmodernism Alastair Fowler, A History of English Literature: “The new avant-garde literature (neo-modernist or postmodernist) partly carried modernism further, partly reacted against it – for example against its ideology and its historical orientation. What it consistently pretended to be (and sometimes actually was) was new. Determinedly self-destructive, it attempted to cut off its branch of the past, by proposing entirely new methods, a fresh ‘syllabus’ or canon of authors (Nietzsche, Freud, Saussure, Proust) and a new register of allusions”. The term ‘avant-garde’ (advance guard, vanguard) is a reference to people or works that are experimental or innovative particularly with respect to art, culture, and politics. Present day novelists (or their publishers) favor realism, but many avant-garde, innovative and radical writers seek to undermine its dominance. Avant-garde represents a pushing of the cultural boundaries of what is accepted as the norm or the status quo. The notion of the existence of the avant-garde is considered by some to be a hallmark of modernism, as distinct from postmodernism. Modernism was shaped by the development of modern industrial societies and the rapid growth of cities, followed by the horror of World War I. In art, Modernism explicitly rejects the ideology of realism. Truth through the ‘senses’ (exterior)

Truth through the ‘mind’ (interior)

Criticism of postmodernism are intellectually diverse, including the assertions that postmodernism is meaningless and promotes obscurantism. Noam Chomsky: meaningless because it adds nothing to analytical or empirical knowledge. He asks why postmodernist intellectuals won’t respond like people in other fields when asked, “what are the principles of their theories, on what evidence are they based, what do they explain that wasn’t already obvious, etc?...If these requests can’t be met, then I’d suggest recourse to Hume’s advice in similar circumstances: to the flames.”

In 2008 Sokal published “Beyond the Hoax: Science, Philosophy and Culture” detailing the history of the Sokal affair. Michael Shermer praised the book as “an essential text” – “there is progress in science, and some views really are superior to others, regardless of the color, gender, or country of origin of the scientist holding that view. Despite the fact that scientific data are 'theory laden', science is truly different than art, music, religion, and other forms of human expression because it has a self-correcting mechanism built into it. If you don’t catch the flaws in your theory, the slant in your bias, or the distortion in your preferences, someone else will, usually with great glee and in a public forum – for example, a competing journal! Scientists may be biased, but science itself, for all its flaws, is still the best system ever devised for understanding how the world works.” Sokal was inspired to submit the hoax after reading “Higher Superstition: The Academic left and its Quarrels with Science” (1994). The authors report an anti-intellectual trend in university liberal arts departments (especially English departments) which had caused them to become dominated by a “trendy” branch of post-modernist deconstructionism. The Social Text editors accused Sokal of behaving unethically in deceiving them. In response, Sokal said that their response illustrated the problem he highlighted. Social Text, as an academic journal, published the article because an “Academic Authority” had written it and because of the appearance of the obscure writing. The editor admitted that was true; they said they considered it poorly written but published it because they felt Sokal was an academic seeking their intellectual affirmation. Sokal stated: “my goal isn’t to defend science from the barbarian hordes of lit crit (we’ll survive just fine, thank you), but to defend the Left from a trendy segment of itself…There are hundreds of important political and economic issues surrounding science and technology. Sociology of science, at its best, has done much to clarity these issues. But sloppy sociology, like sloppy science, is useless or even counterproductive”. “Higher Superstition” argued that in the 1990s a group of academics whom the authors referred to collectively as “the Academic left” was dominated by professors who concentrated on racism, sexism, and other perceived prejudices, and that science was eventually included among their targets – later provoking the “Science Wars”, which question the validity of scientific objectivity and the shortcomings of relativism, that postmodernist critics know little about the scientific theories they criticized and practiced poor scholarship for political reasons. In “Beyond the Hoax”, Sokal maintains that it is “important not to confuse facts with perceptions of facts and actual knowledge with purported knowledge”. The Paranoid Style

“Silly boy ya’ self-destroyer.

Paranoia, they destroy ya. Self-destroyer, wreck your health. Destroy your friends, destroy yourself. The

time device of self-destruction – lies, confusion – start eruption” – “Destroyer”, The

Kinks

In “The Paranoid Style in American Politics” (1964) American

historian Richard Hofstadter uses the (pejorative) phrase "paranoid style" to describe political personalities

linked to conspiracy theories and "movements of suspicious discontent" within American history.

Influenced by Franz Neumann's "Anxiety and Politics" (1954), Hofstadter attempted to tie 'status anxiety' to

'interest politics'. A 2022 Amazon review of “The Paranoid Style” comments: “What’s missing from the paranoid style is not facts, but sensible judgments. Postmodern

constraints on thinking demand moral relativity and decree that all truth is subjective. Postmodernism

practically celebrates paranoia, projection, denial and distortion as undeniable and fundamental

truth.”

During the 1980s passionate lines were drawn in academia over the issue of can natural scientists speak authoritatively on whether history, philosophy, sociology and the other practitioners of the humanities have anything “interesting to say about the efficacy of the scientific enterprise”. In hopes to bring the “realists” and the “postmodernist” camps together, scholars from the diverse fields of physics, history of science and literary theory were invited to the 1997 Southampton Peace Workshop. One outcome was the book “The One Culture?: A Conversation about Science” (2001). The book’s title is a reference to C.P. Snow’s “The Two Cultures” (science versus the arts and humanities). The Southampton workshop’s conciliatory tone was in stark contrast with other ‘science wars’ forums, where opposition was usually absent and the purpose basically came down to a public display of scorn. Unsurprisingly, there are no simple

solutions. Even assumptions were challenged: many of the participants didn’t agree that war was going

on and if there was one, it didn’t make sense to declare a truce. Some positive ‘take home messages’ did

emerge. Out of his arguments with sociologist of science Harry Collins, theoretical physicist David Mermin

came up with a set of simple "lessons learned": Amazon Customer Review. Reader Benjamin

B. Eschbach's makes an astute observation on “The One Culture”: One of the remaining sticking points from the Southampton workshop concerned education -- whether science and critical thinking should be in the forefront or whether education should be more rounded. It can be argued that C.P. Snow’s “Two Cultures” will always be with us. Hopefully future ‘peace workshops’ and integral meditations will bring a truce to the fight over science. In “Making Social Science Matter: Why social Inquiry Fails and How It Can Succeed Again” (2001), Oxford University economics professor Bent Flyvbjerg argues that the social sciences have failed as a science. Professor Flyvbjerg identifies a way out of the Science Wars by arguing that: 1. Social Science is phronesis and Natural Science is episteme, in the classical Greek meaning of the terms. 2. Phronesis is well suited for the reflexive analysis and discussion of values (axiology) and interests, which any society needs to thrive. Episteme is good for the development of explanatory and predictive theory. 3. A well-functioning society needs both phronesis and episteme in balance or in harmony. One cannot substitute for the other.

|