Justified True Belief (JTB)

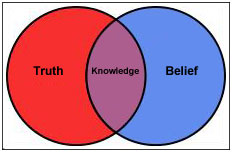

The traditional definition of propositional knowledge is derived from Plato's Socratic dialogue ‘Meno’ and ‘Theaetetus’ where Socrates proposes that knowledge has three essential components – “Justified True Belief” (JBT). Many people have an intuition that the statement “Knowledge is more valuable than mere true belief” is true. The relationship between belief and knowledge is that a belief is knowledge if the belief is true and if the believer has a justification (reasonable evidence) for believing it is true. It is important to note that JTB isn’t an “official” definition of

knowledge, it’s a rough description of a general conception of how certain types of propositional knowledge

might arise. Belief The concept of belief presumes a subject (the believer) and an object of belief (the proposition). Knowledge is a mental state. Knowledge exists in one’s mind, and unthinking things cannot know anything. Knowledge is a kind of belief. If one has no beliefs about a particular matter, one cannot have knowledge about it. Truth If a belief is not true, it cannot constitute knowledge. Accordingly, if there is no such thing as truth, then there can be no knowledge. Justification The requirement that knowledge involve justification does not necessarily mean that knowledge requires absolute certainty, however. Humans are fallible beings, and fallibilism is the view that it is possible to have knowledge even when one’s true belief might have turned out to be false. Gettier Case – The Broken

Clock There is a classic challenge on justified

belief. Suppose that the clock on campus (which keeps accurate time and is well maintained) stopped working at

2:30am last night and has yet to be repaired. At exactly twelve hours later, you lock at the clock and form the

belief that the time is 2:30pm. Your belief is true since the time is 2:30. And your belief is justified, as you

have no reason to doubt that the clock is working, and you cannot be blamed for basing beliefs about the time on

what the clock says. Nonetheless, it seems evident that you do not know that the time is 2:30. If you had walked

past the clock a bit earlier or a bit later, you would have ended up with a false belief rather than a true one.

This is an example of an ‘academic’ Gettier case in which one can have JBT but not

knowledge.

|