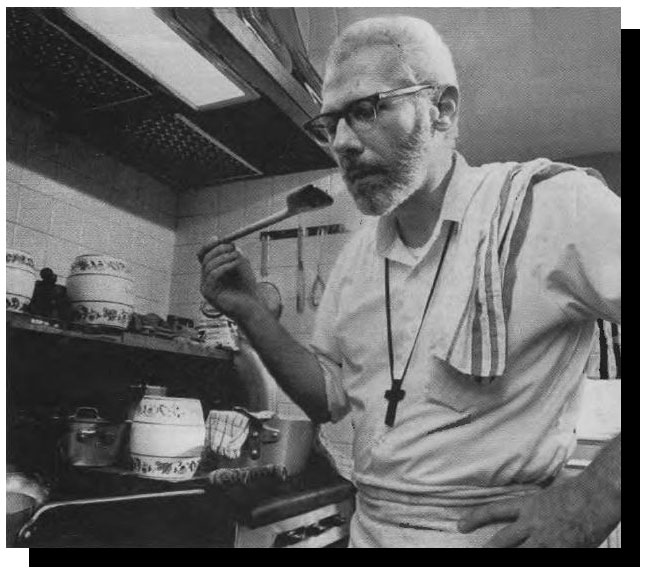

Robert

Capon

Knives mattered. No man should be without a pocket-knife, preferably gold-handled. How else would you peel an orange, or cut a sprig of privet blossom for your second-youngest daughter? A blunt knife was not just a bad way to hurt an onion, but sacrilege, an insult to God’s creation, its beauty and its excellence. Robert Capon could spread scorn as liberally as his beloved butter. Appetizers before dinner, for example, were anathema: they should be called “de-appetizers”, especially when served with cocktails. They blunted hunger’s edge as surely as chopping on the wrong surface would ruin one of his precious carbon-steel (never stainless) blades. Food, he believed, shaped and reflected the way you live. So aim high: why bother with second-rate ingredients, gimmicky gadgets and rushed preparations when providence has ordained such enjoyable alternatives? He told his readers to save money by throwing the junk food (such as supermarket cheese with “the texture, but nowhere near the flavor, of rubber gloves”) out of their shopping basket. Then they could buy something decent instead – such as the best available butter. “The realm of the irreplaceable is no place to count cost,” he wrote in “Supper of the Lamb”, a metaphysical treatise on cooking published in 1967 and popular ever since. Better still, head for the butcher, and haggle over a really big leg of lamb, a colossal loin of pork, or half a dozen cut-price chickens. Then the fun starts: boning (those knives again), browning (no flour, please) and roasting (try it, Swedish-style, with sweetened milky coffee) or casseroling (emphatically no water, just stock or wine, or preferably both). He had no truck with American abstinence. “God invented cream. Furthermore, having made us in his image, he means us to share his delight in its excellence,” he wrote. He liked a drink or two as well: a married couple’s half-bottle amid meatloaf and brawling children was one of the “cheerful minor lubrications” of the “sandy gears of life”. But modern-day American, he wrote glumly, “drink the way we exercise: too little and too hard.” He knew how to dine out, too. Carve gracefully when asked, discreetly sharpening the knife on the back of a roasting tin if necessary. And in restaurants, order something that has involved real work, not just reheating or frying. Cassoulet, Chou croute garni and tripes Nicoise promise “more of the cook’s mind and heart than tournedos ever could”. And, if you can, try the starter before you choose the main course: it will give you an idea of how to proceed. Yet he neither preached nor practiced perfection. For all his fame as a cookery writer in the New York Times and elsewhere he was an amateur, he insisted: an experimenter not an expert. Recipes are like flying buttresses, you find out whether they work only by trying them out: no soufflé sandwiches, no Chartres cathedral. Eaters should be adventurous too. A diet must perhaps be balanced, but only “unbalanced tastes” allow you to enjoy the astonishing oddness of the world. He cherished a bottle of loathsome chemical kirsch, sipping it as a reminder that nasty flavors have no limit. Casualness, though, does have its limits. Dinner parties, for example, are an act of love. So think hard about the mix of guests and their seating, and serve dishes you have cooked before. Flavor trumps hygiene: a precious iron pan or wok should be wiped, not washed (and tell complainers that you are working on godliness now, and cleanliness can wait). But only your family may be teased with a cigar wrapper in the casserole, or a match in the gravy. Entertaining need not be fancy, of course: the single greatest temporal blessing, he wrote, was a long evening of old friends, dark bread, good wine, and strong cheese. Mr. Capon had no time for strict scorekeeping, in the kitchen or anywhere else. Grace, not willpower, dealt with sin: Jesus came to save the world, not to judge it. Showy piety, legalism and quietism were all abominations, almost as much as the cheap oil and harsh flavors of phony ethnic food. His own scorecard had some blots. Divorce from the mother of his six children cost him his parish on Long Island and his post as dean of an Episcopalian seminary. His 27 books (mostly on theology) and cookery columns only partly filled the gap. But there were worse things than being poor, he wrote, such as losing sight of the greatness of small things. At a posh church in East Hampton, he started his sermon by burning a $20 bill, with the words: “I have just defied your God.” Ministry of

food z

|