Friedrich Schelling

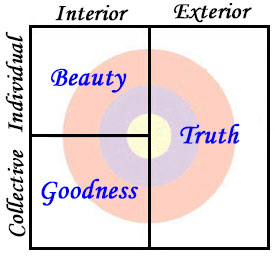

Friedrich Schelling (1775-1854) was a German idealist philosopher. Standard histories of philosophy make him the midpoint in the development of German Idealism, situating him between Fichte, his mentor prior to 1800, and Hegel, his former university roommate. Schelling's works were generally neglected due to being in the shadow of Hegel and his lack of ‘empirical orientation’. Schelling was influenced by the Jena Romantics (1798-1804) and their mandate: “All art should become science and all science art; poetry and philosophy should be made one.” Schelling developed a unique form of Idealism known as Aesthetic Idealism where he espoused the idea that only art (‘Beauty’) was able to harmonize and sublimate the contradictions between subjectivity (‘Goodness’) and objectivity (‘Truth’). Schelling’s Idealism established a synthesis between his conceptions of nature and spirit. Schelling’s Aesthetic Idealism is visually illustrated using Integral Theory’s AQAL map:

Walter Schulz (1912-2000), one of the co-founders of the 1954 international conference in honor of Schelling’s centennial death, published a book claiming that Schelling had made German idealism complete with his late philosophy, particularly with his Berlin lectures in the 1840s. Schulz presented Schelling as the person who resolved the philosophical problems which Hegel had left incomplete. In "Nature is the Poetry of Mind, or How Schelling Solved Goethe's Kantian Problems" author Robert Richards expounds on how Schelling made an impression of Goethe: “Schelling held that the ultimate aim of transcendental philosophy was to bring to intuitive identity the conscious and unconscious activity that constituted the unity of the self. With Fichte, he rejected the Kantian notion of a thing-in-itself as inconsistent and unjustifiable. He rather argued that the unconscious activity of an absolute self-created both an empirical self and nature as the self’s reciprocal correlate. Transcendental philosophy had the task of making this creative activity reflectively certain on the one hand, and, on the other, to unite in intuitive synthesis both nature, the unconscious product of self, and the conscious self, which stood over against nature — the objective realm with the subjective, necessity with freedom. The philosopher had the task, therefore, of bringing the intellectual intuition — that activity productive of self and non-self — up from the darkness of unconscious operation into the light of reflective awareness. But this intellectual intuition, according to Schelling, could be most perspicuously modeled on the aesthetic act, which united the unconscious laws of beauty and the conscious intentions of the artist. Close examination of the creation of the aesthetic object by the artist of genius, then, might illuminate the creation of the natural world and the empirical self by the genius of the absolute self. Schelling’s own

theory of genius depended upon ideas drawn from Kant, Friedrich Schiller, and Friedrich Schlegel. He interpreted

Kant’s definition of genius to mean that the artist’s unconscious nature determines those principles of beauty that

express themselves in non-conceptual feelings, which, in turn, drive conscious actions. The artist applies paint to

canvas not in light of a conscious set of rules but by relying on aesthetic feeling—the palpable surface of

underlying unconscious laws — to guide the brush.” During the environmental concerns of the 1970s philosophers became attracted to Schelling's single-system philosophy of nature (‘eco’) and the intellectual (‘ego’). His influence and relation to the German art scene, particularly to Romantic literature and visual art, has been a scientific interest since late 1960s, from romantic painter Philipp Otto Runge (1777-1810) to visual artist Gerhard Richter and experimental artist Joseph Beuys (1921-1986). American philosopher Key Wilber places

Schelling as one of two philosophers who "after Plato, had the broadest impact on the Western

mind".

z |