Emile Zola (1840-1902) Emile Zola’s father, Francesco Zolla, was born in Venice, Italy. During Napoleon’s takeover of Europe, Francesco joined the army as a 2nd Lt. Took a degree in mathematics; studied military engineering. When Austria took over Venice from Napoleon, life under foreign powers become too difficult. Zola left Italy never to return. Francesco worked during the booming civil water work projects in Marseilles, France. He married in 1939 (age 44) to a 20 year old Parisian woman – Emillie Zola. Emile Zola was born in Paris in 1840. The Zola family relocated to Aix en Provence in southern France. Francesco won a contract to build a water canal. Life was fairly prosperous for the Zola family until Francesco suddenly died. For years, Emillie became embroiled in many legal battles with the canal company. During his school days Emilie befriended fellow classmate Paul Cezanne, who became a lifelong friend. Cezanne was noted to have a difficult and prickly personality (underscores Emilie sensitive personality). Cezanne was permanently locked in battle with his wealthy father who was derisive about his ambition to be an artist. For Zola the countryside and the city of Aix itself became the inspiration of his future novels. Victor Hugo was one of Zola’s idols, but it was the romantic poet Alfred de Musset that was the dominate influence for Zola and Cezanne. Musset was much less tyrannical than Hugo. Emilie and his mother moved to Paris. The demand of Paris schools were greater than the schools of Aix. At the Lycee Louis le Grand Emilie failed in his final exams and his baccalaureate. He tried again at a school in Marseilles. He failed the baccalaureate again. Paris and poverty loomed large for Zola and his mother. Zola took on several odd jobs, one as a civil worker at the patent department. Years later he found work in the distribution department of the French publisher Hachette. Zola rose from clerk to director of the publicity dept. then to the advertising manager. Through his work Zola made important literary connections and developed a talent for publicity. Zola began writing for journals and newspapers. He a Cezanne visited the studios of Renoir, Bazille, Fantin latour, Monet, Degas. Zola honed his skills as an art critic. Zola’s 1st published work: “Les Contes a Ninon” (Stories for Ninon). Writers were typically paid only once for the 1st printing. The publisher took all the royalties after that. In a successful work, all the profits stayed with the publisher. Zola arraigned a royalty on the sales after the 1st run (1500 copies) – it was this initial business savvy (& confidence in his work) that would prove to be the source of Zola’s future wealth. Zola’s 1st novel: “La Confession de Claude”

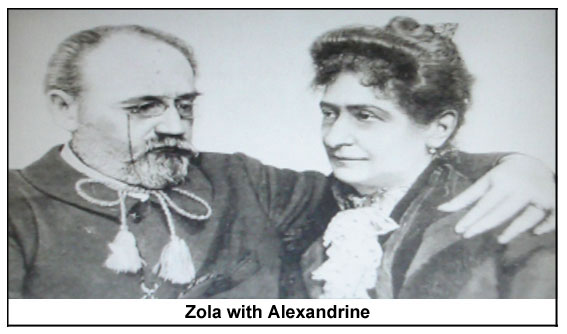

(The Confessions of Claude, 1865) 1866 – Zola leaves Hachette to pursue his writing career. Zola married Alexandrine, a supportive wife who bolstered his confidence and restrained his foolishness. Unfortunately the couple were unable to have children. As art critic in a local newspaper, Zola promoted Manet and other artists. People were scandalized by Manet’s “Dejeuner Sur e’Herber” (naked lady with dressed gentlemen at a countryside picnic).

Zola financially supported several aspiring artists. He gave 60 francs a month to the improvised Cezanne for many years. Cezanne’s wealthy father would not support him.

Zola became the subject of many cartoons.

Victor Hugo, the greatest of romantic writers, rarely moved from his study when he wrote, relying on his imagination and his memory for the background to his stories. Zola’s approach, while, of course, ultimately producing imaginative work, always started with some deliberate research. It helped his realism.

Zola researched the new department stores or ‘Emporiums’ out of which became the story “Aux Bonheur de Dames” (To the happiness of Women).

Zola’s greatest success in novel writing was the development of a succession of linked novels. Zola wrote 20 novels based on two families: the Rougons and the Malquarts. The Rougon-Malquart series ran from 1871 to 1893. It followed the ups and downs of the families, usually locked in enmity and torn by adversity. Zola’s imaginary map of Plassans was very close to childhood Aix en Provence. Zola’s work did financially well in adaptations for theatrical plays. He became known worldwide. He purchased a country home in Medan.

Soon, Zola discovered what was missing in his life – a family.

He fell in love with Jeanne Rozerot – the home’s chambermaid. They had two children.

Zola told his Alexandrine that he would not leave her – she was good to him. She eventually acknowledge his children.

After the 20 novel series Zola began “Les Trois

Villes” (The Three Cities): He began with Lourdes because he saw the pilgrimages their – the calculated fraud on the part of the Church. Emotional capital was being squeezed out of the sufferings of the poor pilgrims who struggled so hard to get there, believing they would be cured. Lourdes is centered on a young priest who begins to question his faith in Christianity. In the novel ‘Rome’ the same priest encounters the scheming of the leaders of the Church for their own advancements. In ‘Paris’ Zola turns his attention to the business world here his contemporaries were so often duped into investing their money in spurious businesses, which spectacularly failed. In 1894, real life in Paris witness the assassination of the President by an anarchist in a wave of business scandals and terrorist acts. Zola’s ‘Paris’ was brilliantly topical. The Dreyfus

Affair Zola ‘fled’ to England. In the eyes of the establishment Zola was poison, but to the democratically-minded, and particularly the young, he was noble. Zola lived in London for about a year while the Dreyfus affair continued to tear France apart. Dreyfus was not just about a Jew who was victimized, but a symptom of the corruption in the French army, bureaucracy and government which Zola so despised.

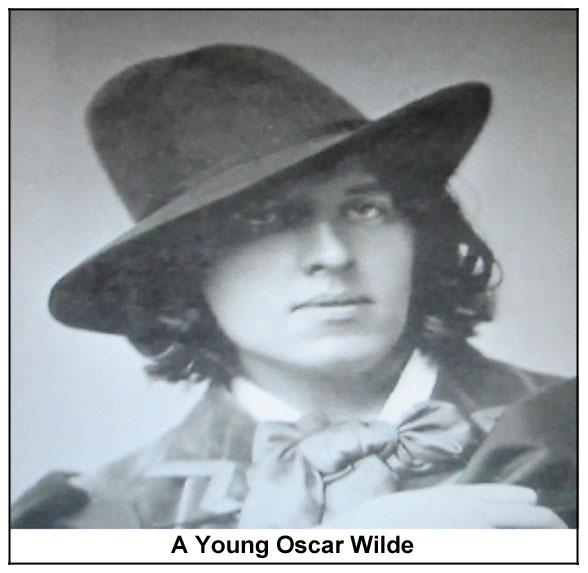

‘We’re all in the gutter, it just that some of us are looking at the stars’ - Oscar Wilde

Zola returned to Paris when a general amnesty

was declared over the Dreyfus affair (1899). He began a new series called “Les Quatres Evangiles” (The Four

Gosples) These novels were typical of the positive, life-affirming, optimistic Zola. Never afraid to uncover the seaming less side of life, but always to believe in the virtuous possibilities of mankind at the same time. Zola’s end was a tragedy. One night at his Paris house his chimney got mysteriously blocked and he and his wife were found the next day gassed by the carbon monoxide fumes from his fire. She recovered, he did not. It was a sudden and unlooked for end and there were suspicions it might have been murder. Certainly there were those who hated his work and his influence so much they might have engineered such a thing. The pen has always been a great deal mightier than the sword and the man of ideas and imagination who could write as Zola could is a great threat to people who don’t agree with him. Zola had a strong social conscious, but he understood too well to preach. Above all he was a story teller of great power and imagination. Through his characters and their lives he entertains and illuminates the minds of his readers today just as much when he wrote. No writer could do more. Zola's Legacy Novelist Tom Wolfe, noted for mocking left-wing intellectuals (“Radical Chic & Mau-Mauing the Flak Catchers”) and glorifying the alpha-male (“The Right Stuff”), has often been labeled conservative or reactionary. His depiction of the Black Panther Party in ‘Radical Chic’ led to a member of the party calling him a racist. Rejecting the cliche label, Wolfe notes that his idol in writing about society and culture is Emile Zola. In Wolfe’s words, Zola was "a man of the left" but "went out, and found a lot of ambitious, drunk, slothful and mean people out there. Zola simply could not — and was not interested in — telling a lie."

In an interview with The Guardian (2004), Mr. Wolfe, commented, "I do think that if you are not having a fight with somebody, then you are not sure whether you are alive when you wake up in the morning."

z |